The Archaeological Survey of India, Keezhadi, Sambhal, and the Practices of Hindutva Archaeology

Archaeology shapes how we imagine the present by helping us understand the past, and it remains a crucial tool for doing so. But in India, it often intersects with Hindutva narratives. From Ayodhya to Keezhadi, this article examines how archaeology is shaped by the contexts in which it is produced.

Introduction

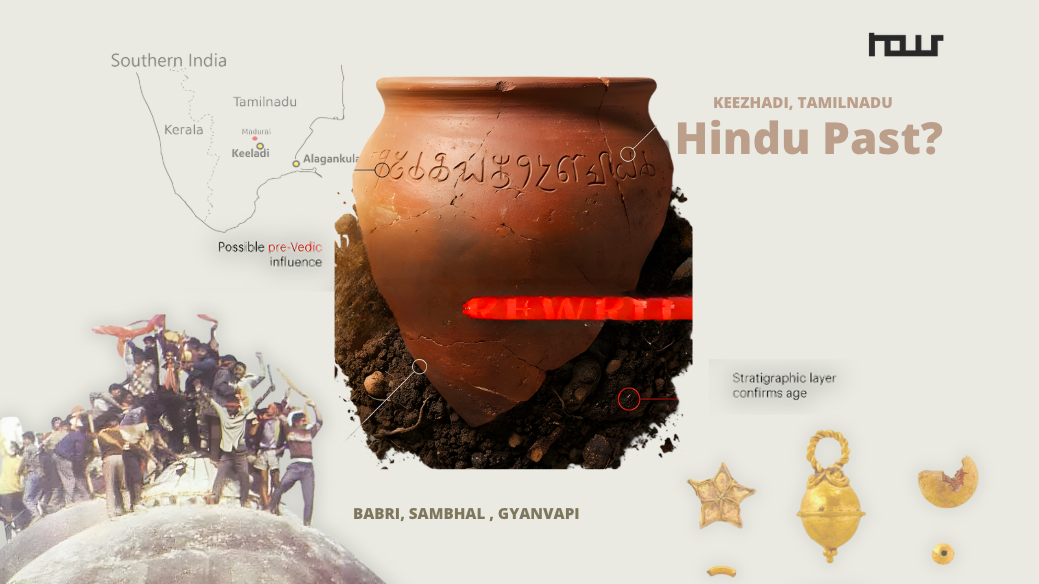

In June this year, the Keezhadi excavations became the centre of a renewed public discourse when the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) asked K. Amarnath Ramakrishna, the lead archaeologist of the project in its initial phases to revise the conclusions of his final report submitted in 2023. The ASI questioned the dating and stratigraphic interpretation of key findings on the grounds that the results appeared “too early” and required further examination and to rewrite the report. Ramakrishna declined, asserting confidence in the methodological rigor of the analysis, and was subsequently transferred once again. The controversy escalated into a visible confrontation between the Tamil Nadu state government, which publicly supported the continuation of the project and later assumed responsibility for subsequent excavation phases, and the central government–controlled ASI. The dispute drew attention not only to the scientific questions surrounding the site but also to the institutional and political tensions shaping archaeological research in India.

To understand why this conflict became significant, it is necessary to return to the origins of the excavation.

Keezhadi, located in the Sivaganga district of Tamil Nadu, first entered the archaeological record in 2015. Over its initial two phases, a team of ASI archaeologists led by Ramakrishna unearthed more than 7,500 artefacts, together with structural remains such as brick walls, drainage systems, and wells.

Radiocarbon analysis dated the settlement to around the second century BCE, corresponding to the early Sangam period. These findings extend the chronology of early Tamil urbanism and show that a sophisticated urban culture in South India developed broadly contemporaneously with, and in interaction with, the early urban cultures of the Gangetic plain and the late/post‑Harappan cultures of the northwest, rather than emerging simply as a derivative of them.

This was particularly significant in a national discourse where the Indus Valley Civilisation has increasingly been positioned as the singular origin of what is framed as essentially “Indian”, including Sanskrit, early Vedic Hinduism, and other contemporary markers of cultural nationalism. Keezhadi’s evidence of an autonomous southern urban tradition introduced an alternative historical trajectory, challenging the narrative of a unified, northern-centred civilisational lineage. Consequently, the site has remained at the centre of sustained scholarly and public debate.

However, the institutional trajectory of the Keezhadi excavations stands in marked contrast to the rapidity and visibility of archaeological activity at other sites. In November 2024, following a petition alleging that the Shahi Jama Masjid in Sambhal, Uttar Pradesh, stood atop a pre-existing temple structure, a local court ordered an ASI survey. The process advanced rapidly: an advocate commissioner was appointed within hours, and preliminary observations were circulated widely in national media even before the completion of formal archaeological documentation.

Mainstream television broadcast these early visual findings under headlines asserting that “temple symbols” had been discovered, effectively transforming tentative, unverified observations into definitive claims of a temple structure.

This framing played a significant role in shaping public perception long before any peer-reviewed or officially sanctioned archaeological report was available.

The rapidity of the survey and the near-immediate publicisation of its results stand in striking contrast to the protracted scrutiny faced by Keezhadi.

The juxtaposition of these two trajectories, i.e., prolonged institutional scrutiny and administrative contestation in Keezhadi, and accelerated action coupled with immediate media amplification in Sambhal, raises a broader analytical question: what governs the production, certification, and publicisation of archaeological knowledge in India?

These cases suggest that archaeology operates not solely as a scientific discipline governed by method and evidence, but also as a terrain shaped by institutional authority, legal intervention, media representation, and political ideology.

This article investigates the Keezhadi and Sambhal cases comparatively to examine how archaeology in India functions simultaneously as a scientific enterprise and as a site of political negotiation over history, identity, and legitimacy.

I. The Archaeological Survey of India: Bureaucracy and Ideology

The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), a government agency under the Ministry of Culture, is formally responsible for archaeological research and the conservation of monuments across India. Its institutional roots lie in the colonial administration. In 1784, Sir William Jones founded the Asiatic Society in Calcutta, bringing together colonial officials and scholars engaged in collecting antiquities and studying India’s past. Over time, the Society undertook surveys, published archaeological reports, and initiated preservation work. This culminated in the formal establishment of the ASI in 1861, with Alexander Cunningham appointed as the first Archaeological Surveyor.

Although this appears to represent a neutral scientific consolidation, scholars have long argued that archaeology has never been ideologically detached. As anthropologist and archaeologist Ashish Avikunthak noted in an interview for this article:

“Archaeological disciplinary discourse all over the world is an ideological discourse. Even scientific discourses have an ideological basis. You might find an object, but how you narrate that object will differ depending on what you have observed and what I have observed.”

In other words, artefacts may be physical, but the narratives constructed around them are contingent, mediated, and politically situated.

Understanding this is essential when examining the contrasting treatment of Keezhadi and Sambhal. If archaeology is not neutral, then the asymmetry between these two cases reflects broader institutional and ideological forces determining what pasts are authorised and what pasts are marginalised.

II. Aryan Racial Theory and the Making of Archaeological Knowledge

If the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) was the administrative structure through which the colonial state studied and managed the past, its methods and priorities were shaped by a deeper set of ideas about race, civilisation, and origin. To understand how these ideas still echo in contemporary archaeology, we have to go back to the late eighteenth century, to the birth of colonial Indology itself.

In 1784, Sir William Jones, a British judge and philologist, founded the Asiatic Society in Calcutta. Jones was among the first European scholars to propose that Sanskrit, the classical language of India, was related to Greek, Latin, and several European languages.

He argued that these languages all descended from a common ancestor that came to be called the Indo-European family. But Jones’s theory was not merely linguistic. Guided by his Christian worldview, he sought to align Indian chronology with the biblical timeline, suggesting that Hindu myths about Manu and the flood were borrowed versions of the story of Noah. He speculated that the earliest speakers of Indian languages were descendants of Noah’s sons, who migrated into India from the West.

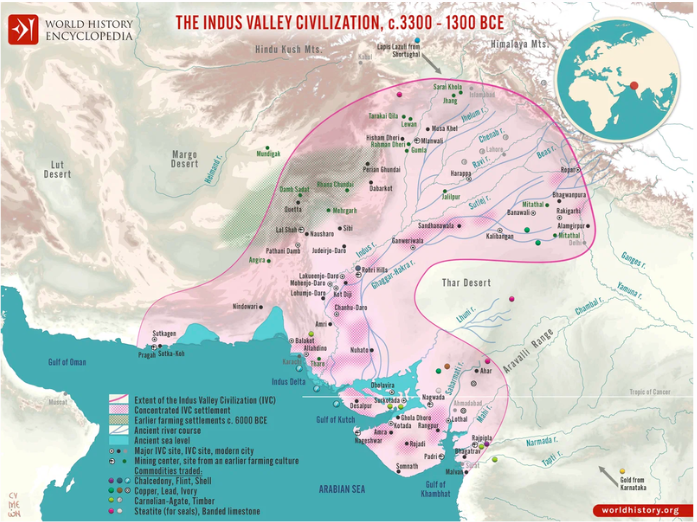

By the mid-nineteenth century, the German philologist Max Müller extended this linguistic hypothesis into a racial framework. Without ever visiting India, Müller proposed that the first speakers of Proto-Indo-European were members of a distinct ethnic group known as the Aryans. He described them as a noble, civilised race whose language and religion, embodied in the Vedas, linked them to Europeans. Over time, the Sanskrit word arya shifted from a cultural descriptor to a racial category. The resulting Aryan Invasion Theory, and its later variant the Aryan Migration Theory, suggested that civilisation in India began when these Aryans entered the subcontinent, bringing with them the Sanskrit language and Vedic religion.

When the Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC) was discovered in the 1920s, it presented a challenge to this model. The scale and sophistication of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro, cities predating the supposed Aryan migration, suggested a complex civilisation already in place before the Vedic age. Yet colonial archaeologists, constrained by racial and textual biases, labelled the Harappans as non-Aryan, thereby preserving the hierarchy that positioned Aryan, and by extension upper-caste, culture at the pinnacle of civilisation. Dravidian-speaking and tribal populations were cast as indigenous but subordinate, while Muslims were portrayed as later invaders, external to India’s civilisational core.

This intellectual framework of reading India through Sanskrit texts, ranking cultures in hierarchies, and measuring progress through proximity to Vedic norms was not just academic. It was institutionalised through the ASI. This is what historians refer to as colonial Indology: a mode of studying India that presented British rule as a rational and modern corrective to a stagnant and divided civilisation. Archaeology thus became a tool of governance, classifying the Indian past in ways that justified imperial power.

The end of colonial rule did not erase this logic. It was, instead, inverted. As nationalist and Hindutva movements gained influence in the twentieth century, the Aryan Invasion theory was rejected not to dismantle its racial hierarchy, but to reverse its direction. The new claim was that the Aryans were not migrants into India but its original inhabitants who later spread outward. This “Out of India” theory reimagined India as the birthplace of an unbroken, indigenous Hindu civilization: indigenious, continuous, and pure.

These ideas continue to shape how archaeology is practised and narrated today. Consider the case of the Harappan civilisation. Its major sites lie in present-day Pakistan and northwestern India, yet there has been a persistent attempt by revivalist scholars and commentators to integrate the Harappans into the Vedic world. In this retelling, the Harappans are recast as the original Vedic Aryans, the bearers of an early Hindu culture whose material remains, from fire altars to seals, are interpreted through Sanskritic symbolism. This view has gained traction in nationalist discourse despite mounting evidence to the contrary. As archaeologist and anthropologist Ashish Avikunthak notes, contemporary linguistic, archaeological, and, most recently, genetic research consistently disprove any direct continuity between the Harappan and Vedic populations.

As the Harappan-Vedic linkage becomes increasingly untenable, a new narrative has emerged to sustain the idea of a Vedic civilisational continuity. In 2018, at Sinauli in western Uttar Pradesh, ASI archaeologists unearthed burials containing copper-covered carts and weapons. A Discovery+ documentary soon followed, featuring ASI officials who presented Sinauli through a Vedic lens, describing its inhabitants as a warrior class, even an elite warrior class, distinct from the Harappans but aligned with the martial ethos of the Rig Veda.

This is where Keezhadi becomes especially significant. It does not fit neatly into the Aryan-Vedic storyline. Instead, Keezhadi reveals a literate, urban civilisation in Tamil Nadu over two thousand years ago, rooted in the Sangam tradition, inscribed in Tamil-Brahmi, and unfolding outside the Sanskritic world. Its material record points to a sophisticated society whose cultural development was autonomous rather than derivative.

In other words, Keezhadi unsettles what both colonial Indology and Hindutva archaeology seek to simplify: the idea that India’s past is singular, Brahmanical, and northern. It reminds us that the subcontinent’s histories have always been plural, linguistically, regionally, and culturally layered.

Today we see two contrasting tendencies at work. Discoveries like Sinauli are swiftly absorbed into the Aryan-Vedic civilisational narrative and amplified through documentaries, press releases, and official rhetoric. Excavations like Keezhadi, which gesture toward alternative lineages of history, face bureaucratic resistance and institutional caution.

That tension lies at the heart of what scholars and critics now describe as Hindutva archaeology: a practice in which excavations, discoveries, and interpretive claims are selectively mobilised to affirm a majoritarian vision of India’s past, one that is exclusively Hindu and Aryan.

III. Hindutva Archaeology & Producing the Past

One of the clearest ways to see how archaeology and politics intertwine in India today is through the Ram Janmabhoomi–Babri Masjid dispute.

In Ayodhya, the stage was set. The Babri Masjid, built in the 16th century, became the centre of a growing claim: that it stood on the exact birthplace of the Hindu god Ram, and that a temple had once been there before being demolished. Versions of this belief circulated since colonial times, but after independence, it began to gather new political force.

By the 1980s, this idea turned into a mass political project. The Vishva Hindu Parishad, backed by the BJP, launched the Ram Janmabhoomi movement, calling on Hindus to reclaim this “sacred land.” In December 1992, kar sevaks, volunteers mobilised by the movement, demolished the mosque.

But that moment did not come out of nowhere. It was built on years of archaeological groundwork.

In the 1970s, B.B. Lal, then Director-General of the ASI, led a project called Archaeology of the Ramayana Sites. The title itself showed the intent: to align mythology with material evidence. In his early reports, Lal said little about any temple remains. But in 1990, just as the temple campaign was heating up, he published an article in Manthan, a journal associated with the RSS, claiming his team had found “pillar bases” beneath the Babri Masjid that hinted at a temple.

This claim was absent from his official ASI reports, never peer-reviewed, and hotly disputed. Yet it spread quickly, and the image of those “pillar bases” became a rallying symbol of proof for the temple movement.

In 2003, the Allahabad High Court ordered a fresh excavation at the Babri site. The dig, described as “the most unusual in Indian archaeology,” was carried out under tight court supervision and heavy political pressure. The ASI’s final report concluded that beneath the mosque were remains of a large, non-Islamic structure.

But this was far from conclusive. Archaeologists Supriya Varma and Jaya Menon, who observed the excavation on behalf of the Sunni Waqf Board, raised serious objections: layers were mixed up, artefacts were selectively collected, and records were incomplete. In their view, the remains could point to smaller shrines, even Buddhist or early Islamic, not necessarily a temple.

Despite these objections, the ASI report acquired disproportionate legal weight. The Allahabad High Court and, later, the Supreme Court treated it as authoritative “scientific evidence.” The Supreme Court’s 2019 judgment conceded that the report did not prove the mosque had been built over a demolished temple, yet it still accepted the finding that a “non-Islamic” structure predated the mosque. But it still drew on the report’s findings, that the land wasn’t vacant, and that a non-Islamic structure predated the mosque, giving weight to the ASI’s conclusions even while calling them inconclusive.

The Babri case illustrates how the ASI, even when producing ambiguous findings, plays a decisive role in shaping both judicial outcomes and public perception. Archaeological “proof” becomes less about science and more about national myth-making.

And this pattern has not stopped at Ayodhya.

In 2022, during the Gyanvapi mosque survey in Varanasi, news of a supposed “Shivling” discovery was leaked to the press before any official report was released. The image of a hidden relic immediately flooded television screens and social media, shaping public opinion long before experts had examined the evidence.

Meanwhile, in Sambhal, the ASI’s survey of the Shahi Jama Masjid was broadcast on TV, with headlines claiming temple symbols had been found inside. The report itself was leaked, not released officially. And just like in other cases, the pattern is familiar: selective disclosure, strategic leaks, and an alignment of archaeological findings with Hindutva political priorities.

By amplifying some discoveries (like alleged temples under mosques) and suppressing others (like Keezhadi’s Dravidian urbanism), the ASI becomes less an institution of history and more an instrument of ideology. Here archaeology becomes a practice where excavations are not simply about uncovering the past but about producing it.

Conclusion: Archaeology, Authority, and the Politics of Verification

Across Ayodhya, Gyanvapi, Sambhal, and Keezhadi, a discernible pattern emerges: archaeology in contemporary India increasingly operates not solely as an empirical inquiry into the past, but as a field through which political power negotiates and legitimises historical claims. What connects these otherwise disparate sites is not the nature of their material evidence, but the differential conditions under which that evidence is authorised, circulated, and rendered credible.

In Ayodhya, archaeological findings were mobilised as juridical evidence, transforming contested and debated stratigraphic interpretations into legally binding certainty. In Gyanvapi, archaeology entered the terrain of media spectacle, where potential findings alone were sufficient to generate public conviction independent of methodological verification. In Sambhal, the rapid involvement of the ASI conferred institutional legitimacy upon a claim that was neither fully examined nor publicly documented. Keezhadi, by contrast, illustrates the institutional consequences when archaeological evidence disrupts the dominant civilisational narrative. Its significance lies not only in its empirical implications for chronology, but in its epistemological challenge to a linear, northern, Sanskritic account of antiquity that both colonial Indology and contemporary Hindu-nationalist discourse have sought to establish as normative.

Together, these cases underscore a broader transformation: archaeology is increasingly repositioned from a discipline of interpretation to a technology of verification, where the function of evidence is less to illuminate the past than to stabilise particular political futures. The role of the ASI within this process extends beyond research and conservation; it operates as a bureaucratic instrument through which the state mediates historical legitimacy, regulating which pasts are rendered visible and which are marginalised.

The politics of archaeology in India, therefore, cannot be understood merely through excavation reports or material discoveries. It must be situated within the institutional, ideological, and media ecologies that shape how the past is produced, circulated, and authorised. The contestation surrounding Keezhadi and Sambhal exemplify this shift, foregrounding archaeology as a site where knowledge and power are co-constructed, and where the struggle over history is simultaneously a struggle over identity, citizenship, and belonging.

Watch the video here:

References

Eram Agha, “Site of Deceit: How the Archaeological Survey of India Fortifies Hindutva History,” The Caravan.

Anne-Julie Etter, Creating Suitable Evidence of the Past? Archaeology, Politics, and Hindu Nationalism in India from the End of the Twentieth Century to the Present.

Cynthia Humes, “Hindutva, Mythistory, and Pseudoarchaeology.”

Ashish Avikunthak, Bureaucratic Archaeology: State, Science, and Past in Postcolonial India, Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Ashish Avikunthak, “B.B. Lal and the Making of Hindutva Archaeology,” The Wire.

Shereen F. Ratnagar, “Archaeology at the Heart of a Political Confrontation: The Case of Ayodhya,” Current Anthropology 45(2), April 2004, pp. 239–259.

Jaya Menon & Supriya Verma, “Was There a Temple Under the Babri Masjid? Reading the Archaeological ‘Evidence’.”

Support Independent Media That Matters

Nous is committed to producing bold, research-driven content that challenges dominant narratives and sparks critical thinking. Our work is powered by a small, dedicated team — and by people like you.

If you value independent storytelling and fresh perspectives, consider supporting us.

Contribute monthly or make a one-time donation.

Your support makes this work possible.